What is it that keeps a community’s identity consistent over time? Is it the people? The place? The culture?

Here at Foster Village in Portland, OR, we’ve had around a 50% turnover rate over the past year. Some long-term residents have moved on to live in rural communities. Some recent arrivals decided that the level of commitment wasn’t right for them.

At times, living in community can seem like a constant game of musical bedrooms, as residents try to settle on living arrangements that will last for the long-term.

Some of our values have remained consistent through that time, but others have come up for debate. Are we still interested in raising animals on the property? Do we want to continue volunteering at the local food co-op? How many nights per week should we share dinner?

Fortunately, we’ve been able to space out new arrivals throughout the year, so that we have time to orient each new member to our current way of doing things. Instead of an abrupt shift when our membership changes, we can pass along some of our traditions, while integrating ideas from newer residents.

But what happens when departing residents want a say in how the community develops? Is it fair for long-term residents to have a larger role in the direction of the community? Since some of our properties are still owned by former residents, these aren’t hypotheticals: our shift to collective ownership will involve the input of new and former residents alike.

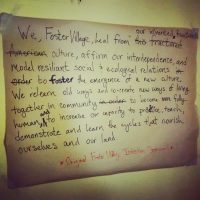

To streamline the process, we created a committee called the “We-Seed,” which will propose a plan for collective ownership of our three houses and bring it to the entire community for consensus. Our criteria for being on the committee is simple: members must have lived in the community for at least one year, and plan to live here for five or more.

These guidelines help ensure that new members can’t hold up the process without good reason, while departing members can’t unduly influence the future of the community. We-Seed meetings are open and transparent, and any of our residents can sit in on them or read the notes.

We’re hopeful that this will honor the values that went into creating the community over the past decade, while being open to new ideas and new ways of doing things.

****

Transitions can be a major turning point for all kinds of communities. When I lived in Los Angeles, I was part of a loose network of collective houses called the BLVD. Since these were mostly rental properties, “long-term” was relative. A house might grow into an 8- or 10-person community only to dissolve once the year-long lease expired.

Still, many of the longest-running traditions persisted: A 4-night-per week meal plan hosted at one of the houses. A regular open mic night that drew dozens of people each month. An e-mail list connecting core and satellite communities.

While it was hard to say what the BLVD was, and where its boundaries began and ended, it served as a hub for nearby residents, and a model for new communities.

During one particularly sudden period of turnover, when half of the residents of a house called Synchronicity moved out, filmmakers Ryan Maxey and Josh Polon captured the experience in a short documentary film called “March.”

Some residents were planning to start a family, or to travel indefinitely. One member was asked to leave. Only one founding member of the community remained.

Luckily, the transition went smoothly: the landlord was supportive, and several of the new residents were already part of the neighborhood network. Having long-term systems in place made it easier to hand over the keys, so to speak, to the next generation of residents.

****

How does your community adapt during times of turnover? What traditions do you have in place for welcoming new members, or to honor the contributions of former members?