Rebecca Mesritz 0:01

Hello communitarians, one of our most beloved guests on the show, Yana Ludwig has just finished writing a new book. And in honor of this new book, we are releasing the interview from last season. This episode focuses on creating a cooperative culture when starting an intentional community, finding your people and coming together with the like minded visionaries that will be your co founders. The book building belonging takes this conversation a step further. It’s both a practical guide for how to start a residential intentional community and a collective framework for addressing the racial, social, ecological and economic disparities that affect all aspects of the living experience for the humans, the land, and all of the cohabitants. Building belonging is available now for pre order at ic.org/building-belonging. But you don’t have to remember that just go to the show notes, and you can click the link and get your copy today. If you’ve already ordered your book and are sitting there waiting for it to arrive, you can go back into last season and I also recorded a bonus episode with Yana where I asked a couple of extra questions, and there’s some really great information in there as well. I hope you enjoy this rerelease of my interview with Yana Ludwig. Welcome back to the inside community podcast. I’m your host Rebecca Mezritz. In this podcast I bring you along for an inside look at all of the beautiful and messy realities of creating and sustaining community. In today’s episode, we are going to continue to explore the process of finding your people how to come together with the people you will be building community with. Now there are many facets to this topic, ranging from how to find your ideal community to how to actually become a really wonderful communitarian. But today we are going to focus on the beginning of the process of starting community, how to come together and join forces with the like minded visionaries that will be your co founders. Here to share her insights on this topic is Yana Ludwig. Yana Ludwig is a cooperative culture pioneer, group process trainer, consultant and anti oppression activist who has lived in community for 25 years. She is the former executive director of both the Center for Sustainable and cooperative culture at dancing rabbit ecovillage and common omics, USA and economic justice organization. And she currently serves as the executive director of leadership Eastside in Washington. Yana is a dynamic, compassionate and thoughtful speaker and teacher committed to creating a world that supports the well being and vibrancy of all beings. Her writings include together resilient building community in the age of climate disruption, published under the name may equate Ludwig as well as the cooperative culture handbook, co authored with Karen GIMP Nick, she has spoken on TEDx hosted the solidarity house podcast, and she was also a candidate for US Senate in 2020. Yana, welcome to the Inside community podcast. It is such an honor to have you.

Yana Ludwig 3:23

Hi, Rebecca. Thanks for having me.

Rebecca Mesritz 3:26

That is quite an illustrious bio there. And I know that as I was reading through it the first time I was like, okay, trying to simplify it a little bit. But you have such an amazing breadth of experience and so many realities, it seems like you’ve danced through so many realities. I really appreciate that you bring all of that skill and insight to the communities movement.

Yana Ludwig 3:51

Yeah, thanks. It’s been interesting. I feel like I’m just sort of creating community and 25,000 different ways throughout my life. So it’s really just variations on that theme for me. So yeah, so it’s been interesting ended up some in some places, I never expected IBM.

Rebecca Mesritz 4:06

Well, I hope that we can touch on some of those places. In this interview today. I usually start my interviews by asking the guest to give us a snapshot of the community that you live in. But I know that right now, you’re not currently living in a community. So I’m wondering if instead, you could just give us a little bit of an overview of what your community journey has looked like?

Yana Ludwig 4:24

Yeah, sure. So yeah, so as the bio said, I’ve been doing community for about 25 years now. And I moved into my first formal intention of community, I had done a little bit of like, you know, group houses and that kind of stuff beforehand. But my first formal, intentional community was in 1996, I was pregnant with my son, and really was kind of dragged kicking and screaming into community the first time by my son’s dad who had spent a year on a kibbutz and was sort of like, oh my god, if we don’t do this community thing now I’m never going to do it. We should go do this. And I was kind of like, there’s no way in hell But I’m going to some stupid hippie commune in the middle of nowhere, I want to go home and hang out with my mom. And so it was not a very smooth start for me with community. But I think the first time that I got there and spent a few days in this space, I started looking around and going, like, Oh, these people are actually figuring out how to do the things that I’ve been talking about in my activism work, you know, they’re growing their own food, they’re doing things cooperatively. They’re finding leverage points around like, you know, gender equality and that kind of stuff. And so I community sold itself to me pretty quickly. And then since then, I’ve spent, you know, I’ve been in eight different communities over the years, and four of those were ones that I was in a co founder role with, and I’d say those four were kind of varying degrees of success. spent the longest time at dancing rabbit ecovillage in Rutledge, Missouri, where I feel like community that’s been probably the most influential on me and my thinking about things of the communities that I’ve been a part of. And most recently, I was a co founder of the solidarity collective, which is an anti capitalist anti oppression commune in Laramie, Wyoming. And so that’s been my most recent home, and when that I still have a lot of connections to and, you know, do a lot of support with and I’m sort of cheering them on now from a distance.

Rebecca Mesritz 6:19

So the Can you describe to me the difference between dancing rabbit and the solidarity house? Like how are those the same? And how are those culturally I guess?

Yana Ludwig 6:32

Yeah, well, so dancing rabbit is it’s an eco village, which means it’s one of those communities that’s really focused on ecological sustainability as a core thing. And so that was their starting point. And, and I don’t think that the founders, when that community started, which was 1997, I don’t think that they really understood that they were going to be doing culture change work, that was something that sort of unfolded over time, you know, they were very focused on like, well, we’re just going to, you know, buy a big piece of property and get 750 people to move there and do sort of a sustainable village together. And that was really what was driving them. And, and the communities, you know, never gotten anywhere close to that big, it’s about. I’m not actually sure what the numbers are right now. But they maxed out at about 75 During the time that I was there. And so culturally, everything that has been learned at dancing rabbit has really come out of wanting to figure out how people actually live together sustainably. And so that was their starting point. And, you know, obviously, coming in as a joiner rather than a founder with that I was able to step into really a fully fleshed out system. So they have, you know, car coops and eating coops and, you know, a whole bunch of different sort of social and physical infrastructure there. And it really is a small village at this point, you know, there’s a b&b, there’s a dance hall, there’s a big common house, you can basically never leave the property and have a really full life at dancing rabbit. Solidarity Collective is, you know, it’s a very new project. We started working on it about six years ago, and they’ve now been on the property for a little over three years. And, you know, we bought an existing property, and it was, you know, a bunch of leftists basically, so, you know, really coming more from a political orientation and wanting to be exploring, socialism, anarchism, communism, and you know, figuring out what we can contribute to moving the political ball in the state of Wyoming to the left. And so a very different starting point. And we also recognize that in order to live a good life, inexpensively, you need to be doing things like growing your own food and putting in place, eating Co Op systems and whatnot. And so like, I feel like in some ways, dancing rabbit and solidarity collective have come to a lot of the same conclusions, but from really different starting places. And, and I certainly brought my dancing rabbit influences with me when I came into being a founder for solidarity collective, so that has something to do with it. But I think it’s also just like you figure out there’s certain basic questions you need to answer. As a community. If you want to do serious work on sustainability or culture change either one of those starting places, you end up asking a lot of the same questions, I think,

Rebecca Mesritz 9:15

Yeah, beautiful. I would love to hear you know, when you talk about those same those lessons learned or those those same questions, can you just outline what a couple of those are for our listeners?

Yana Ludwig 9:28

Yeah, well, so I have a lot of influences from the global eco village network. And there’s a curriculum that Jen was part of developing, called the Gaia education curriculum. And the way that that curriculum breaks it down is basically that there’s four sort of, you know, domains or dimensions, I think, is the language that they actually use in the curriculum of sustainability which are worldview, social, economic and ecological. And the curriculum came out of eco village educators from all All over the world who, regardless of the political or social or climatic situation that they were in, really figured out at some point that like you couldn’t make real progress on sustainability without touching on all four of those, like, if you don’t have a worldview, that’s compatible with sustainability, you’re just not going to have the motivation to be making those changes. You need to be doing things cooperatively, you know, the hyper individualism of the United States and a lot of other countries is not very compatible with actual real sustainability. So you’ve got to be asking social questions and figuring out how to cooperate. And then of course, you know, the economic paradigm that you’re in makes a big difference with how far you can get on sustainability. And so I think it’s, you know, really asking, like, what’s our worldview? What are the motivational underpinnings, the, you know, our ways of putting together the world as far as our mental paradigms? What are those? How willing are we to cooperate? Are we willing to get out of our Everybody’s got their own house and their own lawn mower and their own lawn? And that sort of, you know, individualistic thinking and actually move into how do we cooperate? How do we combine our resources to be able to be doing effective sustainability work? And that gets you into economics? And, you know, are we going to hoard money for ourselves? Or are we going to actually, you know, share those resources and be able to be working together in some economically cooperative way. And when you do those three layers of work, it’s actually very easy to put into place sustainable systems, you know, a lot of the resistance that we have to sustainable systems are actually embedded in one of those earlier, dimensions, one of those earlier stages. And so, you know, I think it’s asking questions, like, you know, where does our power come from? And who does that affect how we’re getting our electricity? You know, are we willing to combine resources so that we can afford a solar power system, you know, most people by themselves can’t afford it. And so you’ve got to come together, oftentimes, as a group to be able to really afford that kind of stuff. So I think it’s those sort of looking at those patterns and what actually leads to a sustainable life. I think, I think those are the kinds of things that I’m talking about with that there’s patterns. So the kinds of questions that you’ve bumped into.

Rebecca Mesritz 12:09

Yeah, yeah. Oh, that’s great. That’s so good. I can definitely see that at the, you know, the Genesis points of the different different people and communities that I’ve talked to so far, about, you know, what is the motivator? And it’s like, looking around like, this is not tenable. We can’t do this is not working.

Yana Ludwig 12:28

Exactly, exactly. Problem Solver nature. Totally, totally. And, you know, nobody creates an intentional community, if they’re happy with what they’ve got, you know, if you look around, and you’re like, Oh, my needs are being met by this culture in the society, like, Why the hell would you do all the work to start an intentional community? I mean, all of us are in it, because we’re trying to do some kind of problem solving and something about that wider culture is untenable for us.

Rebecca Mesritz 12:55

Yeah, I guess, on the on the tail end of the holidays, and all of that I’m just really struck by, you know, looking around and seeing how many people it seems, even if it’s not, quote, unquote, working for them believe that it is somehow working for them? Like, we kind of get a what is it bill of goods or whatever that says that if you have X, Y, and Z, you will be happy. And this is what that is, like, you know, this size house and this kind of car and, you know, this many weeks of vacation, and that equals some kind of happiness factor.

Yana Ludwig 13:34

Right, right. Well, it’s a it’s a word in the American dream. Yeah, yep. Yeah. Sorry. Sorry. Go ahead. Go ahead. No,

Rebecca Mesritz 13:41

it’s just interesting to I’m just reflecting on that now about how Yeah, some of that stuff’s getting unpacked, it seems because we’re realizing through these different diversity and equity movements that have really gotten a lot of traction in the last couple years that even if you do have all that those things, even if you do have that, that house and that car and that vacation and those things, that that doesn’t, it’s it’s actually not sustainable. You know, there’s actually a cost, like we think that we think that we’ve paid that price, but we’re not realizing that we haven’t even come close to paying the price for those things because the ecological and social damage that those freedoms have, have run us really kind of puts puts everything in an imbalance. So

Yana Ludwig 14:32

yeah, it does, does and I think we’re at a really interesting pivot point, because I do think that that, like the sort of gloss on the American Dream has rubbed off for a lot of people. And I think, you know, we’ve got a whole generation of folks coming up who are like, you know, my son is 24. And so I feel like his generation and the generation coming up behind him, like, they see through the fact that like, you can’t actually get it like most people are not actually able to achieve the American dream at this point. And so, so then what do you do? And and it’s a really interesting point, because, you know, in the sort of historical moment, because I think we have a critical mass of people asking those questions right now who don’t buy that, you know, having a good job is the ultimate reason to be alive. You know, there’s all these memes out there right now about like, you know, you weren’t intended to work 40 or 50 hours a week, have like three years of a good life and then die. Like, that’s not why we’re here. Like, there’s gotta be more to it than that. And I think that, that’s a really easy, so I think, for young people right now. And so it’s actually a pretty exciting moment to have kind of an eagle’s eye view of the community’s movement and be watching how many more people are going like, oh, there’s some options out here. And we could actually be leaning into those. And that’s been one of the really fun things is working with groups that are, you know, mostly younger people who just like, they never just bought into the bullshit. And so now they’re like, Oh, now let’s try to create something new. And that’s pretty exciting to be watching.

Rebecca Mesritz 16:01

Huh? Yeah, yeah. Um, so I, it’s one of the things I love about being alive right now is that we get to watch, we’re getting to really watch some major systemic changes, I hope start to take take hold. Well, you know, that does bring me to our topic today about getting started with the community and finding your co founders. And for people who are out there who are saying this is no longer a tenable solution. And they’re looking around now you’ve been through this process four times of CO founding. And let’s just start at the beginning. What are you looking for in your co founders? What are the qualities of the traits that you’re identifying in, in the groups that you’ve had the most success with? And also, what are the red flags? Hmm,

Yana Ludwig 16:51

yeah, really good questions. So I think that, like one of the things that I think is important to understand about the founding process is that I think starting an intentional community is different than just about any other kind of startup project that you could be involved with. And I tell people, and this is a little bit snarky, but it’s, you know, I feel like starting a community is a little bit like starting a nonprofit organization, because it’s very mission driven, you want to do something in the world, you want to change something, that’s usually what nonprofits are about starting a small business, because there’s all of this business planning and marketing and legal stuff that you need to navigate, doing a really intense personal growth course, that’s going to last for many, many years. And it’s also kind of like getting married, because you’re making a really deep relational commitments, people, but you’re doing that with the same group of people. And, you know, you can probably think of people you’d be happy to start a business with, but wouldn’t want to be married to and you know, vice versa. And actually putting together that group, that initial founding group is really important to have people that you actually trust on multiple different levels. And it doesn’t mean everybody has to be really strong at business, or everybody has to be like, an experts, like, you know, like relational ninja or something. But it means that you’ve got to be able to find a group of people that for your initial core group, where you’ve got enough trust in all of those different areas. And so I think sometimes people get frustrated about like, well, I thought somebody was going to be a good match. And then they weren’t, it’s like, well, I just want to validate people, this is really hard. And actually finding that sort of magic mix of people can be really difficult. And so if that, you know, sometimes the hardest step is actually finding your and I would say you want three to eight people in your initial core group, you know, three people is enough that you’re going to have skills variation, and you’re going to have perspective variation, where it’s not just what’s rattling around in one person’s head, or the skills that I have as an individual, but you’re actually being able to, you know, get some variation with that. And more than eight people can be too many cooks in the kitchen for the initial phase of things where you’re having to make some really big decisions about what is our vision, what’s our mission? You know, where are the boundaries of what we’re doing? And I think, you know, sometimes people think, well, I’m going to gather together 20 people, and then we’re going to all figure it out together. And that rarely actually goes well, when you try to do it, that many people and so, you know, gathering together about three to eight people who, you know, have enough of the different skills that we’re looking at. And, you know, and there’s a lot of different things that go into it. And nobody is good at all of this stuff. And it’s part of the reason why you need a group rather than trying to just do it as like a sole founder. But, you know, it’s like things like, you know, being empathetic and listening well, but also having like, you know, some good writing and public speaking skills and having a good head for numbers and having the kind of I’m going to do whatever it takes a vibe to things and at the same time being pretty even tempered without being comfortable with conflict. And I’d say in the historical moment that you were in having some savvy about oppression dynamic Next, you know, understanding business planning, understanding legal systems, I mean, all of that stuff goes into having a really good founders group. And you don’t need everybody to have a head for numbers, but you need at least one person who does and who can explain it to other people and bring them along. You don’t need everybody to be an excellent conflict mediator, but you probably need a person in that initial group who’s good at that kind of stuff. And so it’s really a mix of kind of soft skills and hard skills to use kind of the business world language with the stuff that I think you need to put it together.

Rebecca Mesritz 20:35

Yeah. Yeah. So in terms of the other side of it, you know, the, the red flags are the things that you would maybe say, Oh, this, we might have to hold off on this person. For right now, are these people for right now? What are the what are the things you see in there?

Yana Ludwig 20:53

Well, I mean, I think they can take a lot of different forms. I mean, I’d say the biggest one is they can’t share power, you know, they’re, they’ve got a little too much of a control need. And, you know, don’t do well, with other people’s visions also being part of what’s happening, you know, the thing about starting a community as that you’re starting a collective endeavor, and people who don’t share power, well don’t do well in community and definitely shouldn’t be part of your founding group, because that is the group that’s kind of gonna set the tone for the community, you know, at least for the first five years, and probably permanently, you know, I mean, the who you get into that group at the beginning, you know, you’ve got to be good enough at playing well, with others, I would say, you know, the social skills are really important at that point. You know, I’d say that, you know, people who have sort of litigious ways of approaching things, you know, we, you know, I’ve lived in community with people, and have actively avoided being a founder with people who, you know, when something goes wrong, their first urges to sue someone like that is a setup for having like a major crisis down the road. And so people who haven’t gotten out yet have that sort of competitive orientation and the like, Well, I’m gonna protect myself at all costs, kind of thinking like, that absolutely does not work and community. I also think that for your founding group, you know, you need people who are risk takers, and starters. And there’s a lot of people who are going to be terrific community members who actually, the founding process is going to be too stressful into anxiety inducing for them. And so if you’ve got somebody who like, you know, this is just, it’s too much, it’s too complicated, it’s feels too risky, like, you know, invite them to hang around at the edges and actually bring them in at the point that you’re ready to buy lands, but like, let them know, you know, if this isn’t the phase that you need to be in, it doesn’t mean you can’t play with us, but it’s probably not the right phase to be in. So I think having some discernment about, you know, what phase you’re in, makes a big difference in terms of who you actively invite in. And it doesn’t mean other people can’t eventually play and can’t live there. Because at some point, you’re going to want the maintainers. And you’re going to want the people who are, you know, who don’t necessarily have that founders urge in them, but are really solid, stabilizing factors. Once you get to that point, like that’s when you want to bring those folks in. That’s another red flag so much is it’s just a discernment piece about when the right timing is with someone.

Rebecca Mesritz 23:21

What I’m hearing you say is basically trying to find your founding group, somewhere between the three to eight person number, you want to have a range of skills, ranging from hard skills, like legal numbers, actual, like building skills of some sort, organizational skills, as well as the softer skills of relating conflict resolution, mindfulness in some way towards oppression, culture, and a willingness to work together to share power. Yeah, am I missing anything in

Yana Ludwig 24:02

there? Well, I guess I would, yeah, I guess I would add to things that are more about the the group itself, and not necessarily about what individuals bring to it. I mean, I think that trusting each other is really important. And that doesn’t necessarily mean that it’s like your three best friends that you’re looking for. And in fact, sometimes that’s a complete disaster if you’re not really on the same page about what the vision is that you want in the community. But, you know, it takes time to build and assess trust levels with people but I do think it’s important that you have some fundamental like, I feel like this person has my back even if we have our differences. And the other thing is something about expectations management like this is a long term commitment to get something off the ground. I mean, the minimum that I’ve seen a community successfully get off the ground is about two years. Typically, it’s more like five to seven years from the time that you start the process and you Having people who are willing to be in it for the long haul is really important. And also having people who are willing to give somewhere between two and 10 hours a week, to the process for that amount of time. So oftentimes you have people who, you know, would be terrific founders in some way, but like, they don’t have five hours a week to be giving anything and so, so really making sure that you’re that you’ve got a group of people who are going to be putting in the same amount of time that you are, like, usually, if you’re the burning soul that gets the thing kicked off, like you’re in it for that long haul. And you need a few other people who are also going to, you know, embody that in terms of the time commitment both weekly and in terms of a number of years that they’re thinking about what it’s going to take.

Rebecca Mesritz 25:42

Yeah, yeah, I’ll say when we, you know, when we founded the Emerald village, we had five couples, and some of the couples had kids, when we started, two of the couples did not, but one of the things that we noticed was that over the course of time, and over the course, especially the early years, different at different points, different people would step up and and take the reins different people would be the like, the hard charger for that period of time. But staying, whatever the lead goose, you can’t always, you can’t always be the lead goose, sometimes you have to fly to the back and let another person be the lead goose in your in your V formation. And so we saw over time, that happen very regularly, that there would be a big push for an event or a project that would get us to the next sort of level of foundation. And then the person who had led that was then I don’t want to say burnt out. But there is a level, there’s only so much that you can give especially when you are also have a career or a family or your own personal projects or things like that they are also trying to nurture and maintain. And so people would kind of step forward and step back. But we did all have one thing, which you did touch on as well, which I think is really important, which is this quality of really wanting to show up and do the work, really being committed to we’re here to do this, there was no one that was kind of sitting on the sidelines, waiting for someone else to come in and save the day, everybody had kind of that bootstrapping. Alright, let’s we’re doing this, let’s go do it. And it was a lot more fun when we all did it together. But we all had that quality, which I think really helped us to get off the ground.

Yana Ludwig 27:29

Nice. Yeah. And that’s also I love the story. It’s also a really terrific story for demonstrating what I’m talking about, about power sharing, like, if you’re somebody who like always has to be the lead goose, like, that’s not gonna work. Like you have to be able to like step back and let other people step up and support other people in bringing their gifts to the table. Like I think sometimes you see people who have been in like a founding process for years, and like, the biggest issue is ego management, that they just can’t step back and let other people get in there and sort of direct the ship for a period of time. And it really doesn’t work. And so it sounds like you all did a really good job with that, like power sharing and kind of step up step back approach to things which is great. That’s a terrific example of what it looks like when it actually works.

Rebecca Mesritz 28:17

Yeah. Yeah, there is something to about the you know, not just the power sharing, but also support the support, like the support role also feels as important, you know, the whoever’s at the front end is the leader of that project. Obviously, they’re kind of getting their way in that in some way. They’re like, they’re, they’re the ones who are taking charge. But that leader person always was open to hearing the feedback and sort of actualizing manifesting whenever you want to call the vision of the group and the supporting roles of oh, okay, so this person is putting all this time into there. So who’s going to watch the kids who’s going to create the meals who’s going to, you know, do these other less glamorous roles that kind of keep all the wheels turning and greased throughout that process? You know, that’s the real that the power sharing, that’s how I always saw that happening, as well as it’s not one, it was never a one man show, even if a person is sort of taking the administrative lead on something.

Yana Ludwig 29:26

Right. Well, and I think I think there’s this image that people have sometimes of like, everybody wants to be in charge. And that’s not actually true. Like, not everybody wants to be the lead goose even for a period of time. I mean, there’s plenty of people that like, what they want to be contributing is that support role and you need that, like, you’re not like it’s not about, you know, I mean, you use the word glamour, I mean, it’s not really about glamorous roles. And I think if you’re in it for the glamour, you’re in it for the wrong reasons. I think, you know, what, what helps you be able to do that step up, step back thing I think is is having some good ego management and not being in it because you’d like the idea of having the label co founder next to your name, like, that’s not a good reason for doing this, like at all, and I know so many people that it’s like, like, they have these self aggrandizing stories about themselves as founders, and it’s like, gross, like, No wonder nobody has ever actually wanted to live with you. And, you know, because like, that’s not a vibe that actually is going to get the thing done. I mean, you’ve got to have, you got to have a motivation for doing this that’s bigger than yourself, ultimately, and, and I think that’s what allows you to step back and also allows you to weather it when, you know when conflicts happen. And I think you know, and it probably isn’t as true with as large of a founder group as you had, but with, you know, when you have a smaller pool of founders, like, you’re going to be the first person who gets blamed when something goes wrong. And like when that moment happens, which is almost inevitable. If your motivation was self serving, you’re just going to crumble or you’re going to fight back, and you’re not going to actually hear the feedback and be able to grow in that moment. And I think it’s really important that you’ve got that orientation to, you know, service and to something creating something that’s bigger than you and whatever your own ideas are about things.

Rebecca Mesritz 31:13

Yeah. Yeah, you know, that that makes me think about just this whole endeavor of, of founding community? Well, first of all, just say, it’s hard. It’s really hard. So if you can find a community to join that’s already up and running, that shares your values and has cool people in it, you should just go. Go do that so

Yana Ludwig 31:33

much, so much. Yeah, well, and let me put a thing in about that, too, is that like, you know, I think that sometimes people don’t want to do that, because they think they have such a specific vision, that nothing’s close, you’re not going to get what’s in your head right now. Like, you’re gonna put in two to seven years, and you’re gonna get something that’s close. And that’s kind of in the ballpark of what you’re thinking right now. But nobody ever gets the exact picture. And like, given that, isn’t it better to just join something that’s close, where at least you can pick the version of close that you’re going to end up getting? And so yeah, I am, I am very pro joining community rather than starting them, in spite of the fact that I’ve found myself in that role multiple times. I think, I think, unless you’ve got a really, really strong founders urge, it is almost always better to go join somebody else’s project than go through all of that work before you get a chance to actually live together. So, yes, so just seconding that thought, like, why don’t we do

Rebecca Mesritz 32:39

this? Yeah, it’s a lot. It’s a lot. Well, you know, and then I wanted to talk for a second about just the experimentation aspect of it, which is, you know, this whole thing of creating cooperative culture, creating a community, creating these ancient yet futuristic ways of being in right relation. There’s, there’s so many templates, but there’s no one template. And there’s so much experimenting that’s happening along the way. And so part of that, you know, is we’re thinking about who’s the lead goose and who’s the supporting who’s in the back honking away and support of the lead goose, is really the willingness to allow it to be an experiment and to stay in that kind of curious mind mindset. Because I think sometimes people who want to have control are afraid of failure. That’s what I that’s, I, you know, what, I’m just going to name myself in this, the reason that I have control the situation is because I want it to succeed, and I don’t want it to fail. And I might feel like I’m seeing something that other people aren’t seeing or that my vision is the right way. And so having a really good process for whether you’re using consensus or consent decision making, or whatever your proposal forming processes, having really good processes, whereby any concerns can be brought to the center can be talked about, and can you can continue to have the good feedback loops and the curious experimentation type of a vibe in your community that lets it be okay if things have little failures, because that’s how you’re learning and you’re failing forward as, as they say these days. Yeah, I just want to put that out there too, for folks. Yeah,

Yana Ludwig 34:23

totally. Well, and the reality is, it’s all experimentation. I mean, even if you’re creating a cohousing community where there are kind of templates out there, and there’s, you know, there’s a model that I think a lot of cohousing groups sort of lean into. You’re doing something that is off the beaten path for whatever country you’re in whatever culture that you’re in, or you wouldn’t be doing it. And so I think taking that attitude that like no matter how much you know, no matter how many books you’ve read, I mean, in my case, like I had been through three prior startup attacks Um, so before I got to solidarity collective and my work in solidarity collective was the most humble work of those four projects. And you know, because there was a lot of like, this is what I think I know, here’s some training, like, Let’s lean into it, but there was a lot of like, I know enough to know that this thing is not going to look like what I think it’s gonna look like, and that I need other people, and that I want this to be a project that’s really alive for everybody, not just a fulfillment of my, you know, I think my first startup attempt was very ego driven. And, and it failed for that reason, you know, it was too much of my ego in there trying to steer the ship. And so, you know, as I went along in those, the progression of those four projects, like I think I got more and more willing to have it be a community instead of an ego trip, basically. And so I think, I think that is really important. And I think that thing about, you know, having some sort of collective decision making and collective process around visioning and whatnot, I think all of that is really important, you know, to have in place, and to be making sure that the people who are steering the ship, you know, that that initial founding group, that they’re learning those skills and modeling those skills, because it’s not as simple as like, you know, you read a little bit about consensus, and suddenly you know how to do it, it really is very deep culture shift to be able to do consensus process really well. And that’s a lifelong learning process. And so I think the more humility that the founders can have about, you know, we want to bring everybody in, and we know, we can screw this up. And we know that we’re all just making it up. So let’s make something up that works for everybody. I mean, that’s really, I think, what the orientation ought to be.

Rebecca Mesritz 36:45

Hey, friends, I hope you’re enjoying the show, you know, I am so honored to engage in conversations like this, and to get to examine and dream into better ways of living together. And I know you are too, because you’re here, please take a moment to visit ic.org/podcast and consider financial contribution to the show, so that we can continue to create this useful and meaningful content for you. And thank you.

Rebecca Mesritz 37:19

You know, over the years at different conferences, or workshops that have either facilitated or CO facilitated, I’ve met a lot of people who’ve been really deeply interested, genuinely interested in building community and starting community, some of them even have the money to get get it started. But a lot of times, I will hear them say something like, Oh, I just can’t find the people to do it with or I don’t know if that’s something that you’ve run across. But I’m wondering, really, what’s your take on on that? Or what’s the next piece of advice for folks who can’t seem to find their founding group or can’t seem to find the people that they really trust?

Yana Ludwig 38:03

Well, I mean, I think that there’s, yeah, I’d have to know more about what the specific things are. But I think some of the patterns that I’ve seen are, you know, that there’s that ego management part that, you know, they just don’t have a good handle on, being able to do power sharing, and being able to let it be a truly collective project that they’re holding really tight to something I once had a group asked me if I could look at their website and sort of help them figure out why they weren’t attracting people. And the main thing on the website was a literal, 30 page document of their vision that was incredibly prescriptive. And, and it was like, all you have to do in the course of reading 30 pages is find two or three things that don’t work for you. And you’re like, nope, not my group, it was like, you know, you’re holding too tight onto the details a lot of times, or there’s sometimes like a lot of, and this is particularly true among people who have money and have land and have resources, you’re afraid of losing it, you’re afraid of giving that up turning over what is sometimes family property to a group. And so you hold on to ownership really strongly and to you know, the sort of the, all of the capitalistic reasons that you got the money in the first place, and you try to like take that into the project and really protect what you already have, and not be willing to actually share that with other people and have a clear agreement about turning the property over to other people or turning the vision over to other people. And so, I mean, the one word answer to it is ego. I think unhealthy ego. I mean, there’s healthy ego where, you know, you’ve got to have enough self esteem to be able to sort of keep rolling with the punches, but it’s pretty easy to, you know, to have too much of yourself in there and not enough of really being open to a collective. So I think that’s the biggest reason that I’ve seen people not get off the ground when they have been And sincerely trying for a long time. It’s like, are you actually trying to do something collective or you’re trying to do your own thing, and you want other people to come join you?

Rebecca Mesritz 40:09

Yeah, I want to build this big vision, I have the land already. And I want people to come. And I want them to build community on my property and help me build up my vision.

Yana Ludwig 40:20

Exactly helped me build my thing.

Rebecca Mesritz 40:23

I’ve definitely met quite a few people who’ve had Yeah, had their own land and want to build community on their land, but it’s still their land, and it’s still their, their thing.

Yana Ludwig 40:35

That’s right. But even, even if it’s not, so say, there’s a situation and I have definitely seen situations where I feel like the founders were totally sincere about wanting it to be shared with other people, they were willing to talk about down the road, selling the property to the group and whatnot. As long as you are still, the sole owner or a couple is still the sole owner of that you can pull the rug out from under people at any point like that is your legal rights in this country to be able to do whatever you want to do with your own property within like, you know, building and zoning code stuff. And even if you would never do that, simply the fact that you can, is going to make it really hard for other people to get invested, whether that’s like literally like with money or with their energy and their time, people are just not going to really relax into being a community, as long as you’re still holding title to the property yourself. So it’s one of those ways that like, best intentions aside, like, you’ve got a lot of legal rights in this country, when you own property that really undermine the ability to create real community.

Rebecca Mesritz 41:46

Yeah, you know, I, there’s a lot, there’s usually a very high need for capital in the early days of finding founding, rather, to get the projects off the ground, you know, you want to buy the land, do you want to buy the building, you want to, you know, you need to be able to qualify for loans, make down payments, on property, cover legal expenses, all of all of those things. And like you just for saying, you know, sometimes the person already has that, and wants to sort of put that out there as their offering towards that venture. And I, I love that. And I really, yes, yes, we need, we need the people to have the haves to help support. But I guess, knowing that you’re a person who’s really passionate about equity, I’m wondering what kind of strategies you can recommend for forming groups to overcome some of these hurdles with income inequality? Mm hmm.

Yana Ludwig 42:40

Well, I think there’s a lot of different ways to approach it. And, and so there’s an article actually, that I wrote in communities magazine about cross class cooperation and acquisition of land and founding of communities. So this is something I’ve thought about a lot. And, I mean, I think the critical things are that you are willing to put it into the group’s hands as quickly as possible, and whether that means you donate it, and you get some really good coaching on what it means to not attach strings to that donation. Or you enter into a really clean contract with the community to sell the land to the community. And it’s a business deal. And you keep it as a very clean business deal. And you don’t have any more control or decision making rights, because the community is buying a piece of property from you than anybody else who you’d be buying property from, I think the critical thing is like, is like releasing that control from your individual domain into the collective domain and finding some way to do that. You know, I also think that it is possible to get loans from people who have who are closely connected to the community, a note a number of groups that have, you know, solidarity collective got off the ground, that way dancing, rabbit got off the ground that way where they took out loans with people, but again, it’s a contract, and it’s very clear. And just because you’re getting the land, or you’re getting the financing from somebody doesn’t mean that you have some rights of control to that other than, like, if the project fails, you want to be able to get your money back. You know, if the, you know, if the land sells, I mean, that’s a totally fine thing to write into a contract. So I think there’s those things and I think there’s also looking at how you structure the economics of the community internally and you know, income sharing is something that scares the crap out of a lot of people because it is so far removed from the kind of individualistic culture that we’ve been raised in. And if you really want to level the playing field, inside a community internally, I’d strongly suggest seriously looking at income sharing, and I was involved. I know people freak out.

Rebecca Mesritz 44:53

I want to do

Yana Ludwig 44:58

Yeah, Well, and interestingly, so I was part of an academic study a few years ago with Dr. Zack Rubin and Dr. Don Willis, I was the sort of, you know, Content Specialist involved with working with these two amazing PhDs, who study community as part of what they do, especially Zack. And and so we did a really big survey study of communities. And one of the questions that we were asking was about satisfaction levels for, you know, people living in community, and what are the factors that go into people actually have a good experience living in a community and a lot of what we learned, I was not surprised by, you know, having some sort of mandatory conflict resolution works having some kind of egalitarian decision making works. However, the third one that was in the top three was income sharing. And I was floored, like I had had lived in income sharing groups, like I’m a fan of income sharing, but I had no idea that it was actually that potent, and so yeah, so I think sometimes people get scared about it. But there’s actually some research out there saying, like, maybe it doesn’t have to be so scary if you set it up, right. So just putting that out. And that, and that’s really a way to like, you know, if you’re serious about equity, income sharing is one of the things that makes the biggest difference in terms of, you know, gender equity, racial equity and economic equity.

Rebecca Mesritz 46:18

Wow. I’m not gonna lie like I can feel my heart racing, just thinking about that is definitely not in my comfort zone. And I have every intention on doing some more, at least a couple of episodes on income sharing, and what does that look like? And what can that be? And for people who don’t who aren’t familiar who are listening, who aren’t familiar with income sharing, there’s definitely some Reese’s resources out there. I don’t know if you have any specifically that you would like to decide for people if they want to jump down that rabbit hole?

Yana Ludwig 46:52

Yeah, well, I think. So the the, and this is confusing, because we have the foundation for intentional community. And then there’s the Federation of egalitarian communities. So it’s the F, E, C, and their website is just the fec.org. So there’s a ton of resources on that website from and for income sharing groups. And so that’s one of the places where you can like start going down that rabbit hole. There’s also been a lot of articles and communities magazine over the years that have been about variations on the theme of income sharing. You know, I’d love to be part of that conversation. If you ever wanted to do a panel interview about income sharing, I’d love to be one of the voices with that, because it’s something that I I lived in my first full on community was an income sharing group. And then I decided I didn’t like it. And I went off into a whole bunch of other kinds of community for a lot of years. And then I came back around to it and had have actually gotten back to a place of going like, actually, I really liked the model, even though there were things I didn’t like about it when I was in my late 20s, when I you know, decided to leave that initial community. But yeah, I mean, I think it’s, I think it’s also really important to like part of the rabbit hole is that that tension that you’re feeling in your body right now thinking about it, like, that’s part of the rabbit hole, like, what’s there? What is that tension about? And really being willing to spend some time you know, getting clear about like, what’s at the bottom of that, for each of us? And is whatever’s at the bottom of that, actually, the world that you want? Or not? And like really being willing to look at that and ask those questions, because we’re at a place where like, we need to shake things up, culturally and economically. And, you know, I’ve never seen more productive conversations about what internalized capitalism looks like, than the conversations that I’ve had with people living in income sharing communities, and actually, like, going through all of that, like, Oh, my God, this is super uncomfortable spot. And then it’s like, well, so what is capitalism done to our psychology? You know, yeah, that we have all of that in there. So, yeah. Well, it’s

Rebecca Mesritz 49:02

I’m glad that this has taken this. This conversation has taken this turn because it actually brings me to a question that I wanted to talk to you about, you know, the tagline for the cooperative culture handbook is a social media, excuse me, a social change manual, to dismantle toxic culture and build connection. And I really love this because in my community experience building connection has been the major motivating force for for doing communities wanting to feel more connected to people the planet, higher power. But the notion of dismantling toxic culture has only really been alive for me for the past few years. Since my own kind of diving into diversity, equity and inclusion work, and I say this totally naming and owning that my privilege has allowed that to be the case in my life. But now that the A curtain has pulled been pulled back. And I can, I can see. I can see the Wizard back there turning the gears, you know, I see this this capital, the capitalist culture, the oppression, culture, all these things that you talk about, and it’s hard to unsee them. And I, you know, I’m curious to know from your vantage point, what you see is the biggest hurdle or blind spot is for communities in terms of escaping that toxic culture.

Yana Ludwig 50:33

Oh, my gosh, well, obviously, I have a books worth of things to say about this. So and we broke it up into 26 different sort of, we were calling them keys, which are sort of like a particular aspect of, you know, noncooperative culture that we were sort of taking apart and then talking about, like, you know, well, what do we ought to be doing instead? I mean, I think the biggest picture answer to that is, we don’t think there’s a problem, or we don’t realize there’s alternatives. And so I think you can only solve something and start taking it apart, if you’re willing to look around and go, like, actually, this culture is not working and what’s not working about it. And so it’s that thing that you just said a minute ago, and that, you know, I share a piece of this, and you know, maybe, you know, a few years ahead in terms of like, when I had kind of a big wake up call about it, but it’s like, you know, when you live in privilege, I mean, essentially, what you’re doing is like, you’re getting the comfortable parts of the culture that we have right now, that works good enough for you that you don’t really have to look at it, you don’t have to question it. And so I think recognizing that, that we desperately need some cultural shift, I think is part of it. And, and I would say I mean, I’m a socialist, and, you know, which is not true for everybody in the communities movements by any stretch. So I’m definitely putting the IANA hat on, you know, really deliberately right now. But, you know, I think a lot of it is that our culture and our economic system, are so intertwined with each other, that questioning some of this stuff, triggers a lot of survival buttons for people, like you, you know, you have to buy into capitalism, in order to survive. But what does that do to your relationships? You know, I mean, if you’re bought into an economic system, where some people have to stay poor and struggling, in order for other people to be able to have the American dream. And we’re not questioning that because we can’t, because it means you won’t have healthcare, you won’t have housing, you won’t be able to eat. That’s a really big motivation to not look at this stuff. And so for me, I’ve gotten to a place where I can’t separate my community work from my politics, like, like being able to be a political is also a form of privilege. Like, you can bet that like big business people and your landlord are not a political, like they’re in there, like making sure that the system continues to serve their interests, rather than yours. And so at what point does it become worth actually starting to take some of that apart and taking the risks that are involved with that. And so, you know, we were just talking a second ago about income sharing about how the body clenches up when we think about doing that, and that clench is that same clench that I think we all have around like, you know, I have to keep running the treadmill in this economic system. And so I think that that’s like, for me, I think that capitalism is the thing that has it pinned in the most tragically and intensively and that it’s racialized capitalism in this country. I mean, you can’t really separate racism, from our economic system. You know, we’re on stolen land. We all interact with infrastructure everyday that was built with labor of enslaved people and continues to be sustained by, you know, things like migrant worker labor, super cheap, you know, like all of our systems, our social systems are really, really wrapped up with our economic system and questioning that stuff is scary as hell. And I think that’s really the thing that has a lot of it pinned down. And again, that’s the IANA hat. Definitely not this is what the community’s movement believes about anything. This is where I’ve gotten to through 25 years of being changed and challenged by living in community has radicalized by politics.

Rebecca Mesritz 54:42

Oh, there’s there’s so many layers in there. Like, I wish you did a whole other hour to like, just talk about that because or maybe five.

Yana Ludwig 54:51

I’d love to I would love to just talk about that for a while. So yeah,

Rebecca Mesritz 54:56

it’s been it’s, I mean, on a personal note, you know, This has been a really big topic of conversation in my reality for the last for the last several years. And I have a sister who’s living with us who’s a part of this project that we’re doing now, who’s extremely passionate about equity and who’s always turning the light on in rooms that I, you know, was kind of totally oblivious to the fact that they were the room was even there. And it is a really painful, it can be extremely painful, you know, it honestly, it brings tears to my eyes, sometimes to think about, like, the depth of some of the, you know, it’s not to point a finger or cast blame, but just to say, Wow, I have these beliefs because of a system. And giving up these beliefs would mean giving up so many other things in some way. But I just want to encourage listeners and people who are here to to just, you know, one of the benefits of being in community, potentially, is that you have the opportunity to have a support network, as you unpack some of these things, if you as founders, especially create a culture that says, you know, what, one of the things that we want to do here is just take a look at it, we, we don’t even have to say that we’re going to change anything, let’s just agree that we’re going to take a look at it. Let’s just Let’s just agree to open our eyes and have honest communication and just talk about how it makes us feel. And I think for especially for people that are of a certain level of privilege, which I think, you know, my understanding of the demographics of a lot of the communities movement is that it is a lot of people of privilege are choosing this this way of life. And so we have the option, we have the opportunity really, to use our privilege to start making these, these deeper levels of cultural change, if we can come together and agree to do it together as well. It’ll have all the more all the more power.

Yana Ludwig 56:57

Yeah, and I think I think it’s great that you’ve brought it in that close, you know that you’ve got somebody in your life who’s really, you know, as you say, pointing out the rooms, and then asking the questions in the rooms and that kind of stuff. I think that’s really important. And I think the other thing that community gives us, and the thing that has really sold me on getting into community and then staying at it is also seeing well, what’s beyond those standard ways of doing things. And just like how good of a life it is when you are being able to create different systems. And so it’s not just about what we give up. And I think, you know, that’s the scary part for people who have a lot of privileges, well, what am I going to give up? What am I losing? But there’s also the like, what am I going to get out of it. And I think that that’s really what has driven me to get deeper and deeper into this work over the years, it’s just that we have more to gain than we have to lose. And you have to take a leap of faith, I think, to some extent with that. But you know, being able to live in a place where I have deep, authentic relationships with the people around me, and I’m actually living with a really low carbon footprint. And so I feel good about my life on a fundamental level, that I don’t feel good about it, when I’m living by myself. And when I’m using a lot of resources to support my more individualistic lifestyle, which is what’s happening right now in my life. You know, it’s that kind of peace of mind is pretty invaluable, actually. And being able to know that you have somebody to go to like, for me a big part of it was, you know, my, my son had seizures when he was a baby. And had I not been living in community where I could literally wake up another mom at four o’clock in the morning and go, I am freaking out. Can you just be with me? Like, like, what is that worth to be able to actually do that and to have the level of connection and mutual support that you get in those moments? I mean, that’s the kind of stuff that, like, you know, being a billionaire doesn’t buy you that, you know, it’s like, doing the hard work of creating community gets you bad. And so, you know, so I think it’s important to look at the other side of the scale to about like, what do we have to gain by doing this really important work? And you know, I said earlier that I tried to talk people out of starting communities, I really don’t want you to not start communities, I want us to have a lot of them want you to know that it’s really hard work, but man, is it worth it? You know, when you actually get in there and are able to actually like have that kind of support in your life. It’s huge.

Rebecca Mesritz 59:35

Yeah, you know, I’m hearing this kind of theme of the intimacy and the connection, that is the real win that you get from this way of being. And I know that in your handbook, you have a lot of activities who are that are designed to kind of build that intimacy and build that connection. And I am the kind of person that really really loves that. I was on I was on our human, that human relations circle and my last community and I will be probably always, but we would play communication games and do things to kind of build that intimacy. But I didn’t notice. And I have noticed that not everybody is designed that way. Not everybody likes to build intimacy, there are people who are going to be a lot more reserved. And also, you know, I know that you kind of speak to different abilities in the handbook as well. And I guess I’m just wondering if you have any advice for listeners, especially as they’re, they’re in the founding process, and they’re trying to build that trust and build that intimacy and build that connection? That if they aren’t a group with someone who maybe struggles with vulnerability, or struggles with some of those things? How can they? Do you have tips for them to start to generate that meaningful connection? Despite maybe different comfort levels with intimacy?

Yana Ludwig 1:01:07

Well, I think I mean, I think that there’s a few possibilities there. I mean, one is some forms of community require higher skill level than others. I mean, there’s, there’s some versions of community where, like, somebody has to be okay with sharing what they think about things, and they don’t necessarily have to be in more intimate connection with each other in order to have it work. And so, you know, there’s a big relationship between what your vision is like, what are you trying to do as a community, what your membership process is, and what your decision making system is, like, those three things should be really tightly connected to each other. And, you know, the more radical meaning non mainstream, the more cooperative culture oriented, the more serious sustainability work you’re doing. And the more intimate meaning things like you’re using consensus, you’re doing income sharing, you might be doing spiritual work together, you know, the more you have those things happening, the more you have to be careful about who you let in the door, because you want people who are down for the work. And it is really hard work. And so, you know, I think that there are some forms of community that they’re basically like, you know, a nice neighborhood to raise your kids in. And it’s like, you don’t have to be that intimate with people to be able to do that. And you don’t have to be that careful about who you let in the door. But I think, if you’re doing more serious work than that, then you are going to have to be careful about it. And I think there’s like some really core social skills that you want to be sorting for in your membership process. And, and I’ll just name those really quickly. And those are, you know, things like, can you accurately hear what other people are saying? Or do things tend to get garbled? Can you communicate well enough? Both what you think and what you feel about things? How do you handle feedback? Like are you okay, hearing feedback from people? Are you comfortable talking about oppression dynamics, particularly somebody who’s in a dominant group? And do they have some kind of personal process that seems to help them in times of tension, and you don’t have to worry about what that process is, for some people, that’s I have a really good therapist, for some people, they have a best friend that they can go to who isn’t in the community and isn’t involved with stuff. For some people, it’s a meditation practice doesn’t matter what it is. But having something I think, is pretty important. And so you know, I think that it doesn’t necessarily help if you’re already living with somebody who doesn’t want to do that kind of work. But I think those are the kinds of things that you should be looking at in your membership process, and making sure that people have at least some minimal skill level with that, and are willing to build more. And so I think, you know, we, part of what we wanted to talk about today was membership process, I think that’s one of the more important things is that you’re checking for social skills, and you’re checking for vision alignments. And, you know, if you are already in a community and you wish you’d been stronger about that stuff, and you’ve got people who are already living there, I think the key with that is to work at building systems around them, that can support them and feeling safer about doing that work. So having good conflict resolution systems, starting to do matter of fact, things like have check ins at the beginning your meetings where and where you get real, and you share what’s going on with you and and you let people have some time to kind of ease into meeting you there. Rather than trying to like force it on people I think is pretty important. And so, you know, I saw some really good stuff. You know, I mentioned dancing rabbit earlier, where I lived for, like, gosh, almost a decade between the different stunts that I’ve been there. And for a long time, there really was no attention on social skills at all. And one of the things that started happening Putting is that people would try to get the whole community to like start doing something, they wouldn’t do it. And then a subgroup of people would just start doing it. You know, it worked with NVC, it worked with reevaluation, counseling stuff where somebody would just start doing it. And they’d get a group of people together. And then those people would start showing up differently in the community, and then that would start rippling out. And then eventually, people who weren’t comfortable with that shift left, and the people who were starting to come into the community, were more interested in doing that kind of work. So you can shift a community’s internal culture over time, without having to get everybody currently in the community to like, agree to something that they’re not ready to agree to.

Rebecca Mesritz 1:05:44

That list was just worth the price of admission. I love that. That’s great. I love that. So good. So so good. What do you wish you had known before you had started this community?

Yana Ludwig 1:05:59

The thing that I didn’t know, that I think got me on the trajectory that got me where I am now, is just how important the social stuff is, you know, I didn’t, it didn’t really understand how hard conflict was how hard real inclusive decision making was. And, you know, at some point, I decided that I needed to learn facilitation and like committed to becoming a facilitator. Because, you know, most, not just intentional communities, but most groups doing worthwhile stuff, period, that fail fail, because we don’t know how to do that basic getting along stuff. And so I think, you know, recognizing, you know, that there are those cultural change pieces, recognizing that we just need much better social skills than we have. At this point. I think that’s the thing that I wish I had been better at when I went into it and wish that I had been willing to acknowledge was actually like a real need, because I think I was pretty dismissive of it for the first few years. And then, at some point, I went, oh, oh, this is actually the thing that is not working, and that we need to have work better.

Rebecca Mesritz 1:07:15

Jana Ludwig, thank you so much for being here with me today and for sharing all of your wisdom. And I feel like we need to talk 10 more times.

Yana Ludwig 1:07:25

That would be Thank you. This has been really fun. Rebecca. Thanks so much for having me.

Rebecca Mesritz 1:07:33

If you’d like to learn more about Jana and her work, you can find her online at Jana Ludwig dotnet. You can find her books, the cooperative culture handbook, and together resilient at the icy.org Bookstore. And if you go to our show notes, we’re going to have a 20% off discount code for podcast listeners when you purchase both of those books together. I also want to mention that Jana has an online course called starting an intentional community that’s just been made into a self paced course that’s really perfect for people who are just getting started with a community project, or who are dreaming about starting one. You can find more information about all of that and learn more about this podcast hosted by the Foundation for intentional community at ic.org/podcast. If you’d like to see inspiring images and video of community life, come find me on Instagram at inside community podcast. I would love to hear from you there. And as always, if this content has been meaningful or useful to you, please subscribe rate review, share with your friends and any folks you know who are curious about living inside community

Finding Community presents a thorough overview of ecovillages and intentional communities and offers solid advice on how to research thoroughly, visit thoughtfully, evaluate intelligently and join gracefully. Useful considerations include:

Finding Community presents a thorough overview of ecovillages and intentional communities and offers solid advice on how to research thoroughly, visit thoughtfully, evaluate intelligently and join gracefully. Useful considerations include:

Our virtual learning center offers

Our virtual learning center offers

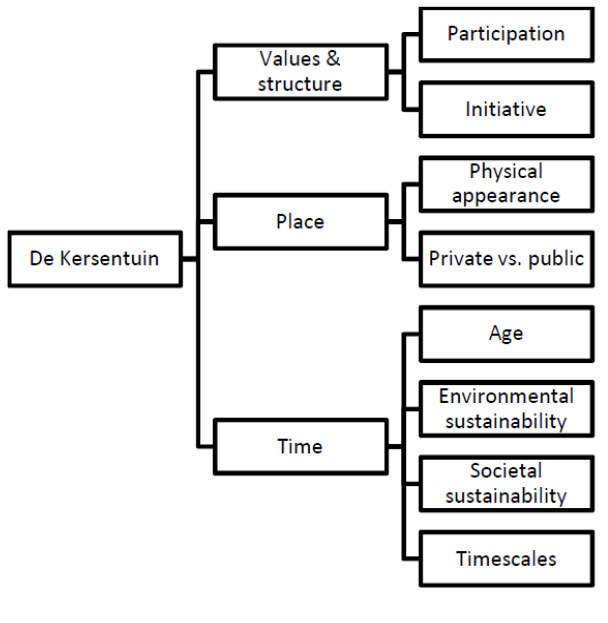

Yana Ludwig

Yana Ludwig