Many of the intentional communities that we hear about are recent ones: the back-to-the-land communes of the 1970s, the student co-ops and cohousing spaces being formed today. That’s why it’s especially fascinating to get a glimpse into a commune from a different era – as I did recently in a book called “Oneida: From Free Love Utopia to the Well-Set Table” by Ellen Wayland-Smith.

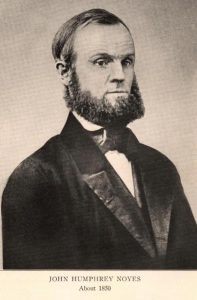

Wayland-Smith is a descendant of John Humphrey Noyes, the founder of the Oneida Community in central New York State. Some of you may recognize the Oneida brand from the silverware company that became a fixture of middle class tables in the post-World War II era. How Noyes and his descendants went from a 300-person, income-sharing commune to capitalist enterprise is one of the most unique tales of intentional living in the U.S.:

“What a strange, dreamlike place America must have been if, for a brief space of time in the 1840s and 1850s, free love and industrial prosperity, communism and capitalism, women’s lib and millennial Christianity appeared to share a sunny future together” (p.6).

Wayland-Smith sets the scene in the midst of the Second Great Awakening, when charismatic leaders began creating their own spin-off faiths, such as Joseph Smith’s Mormonism. John Humphrey Noyes subscribed to a millennialist version of Christianity called “Perfectionism,” in which Jesus had returned to earth in AD 70, and it was up to believers to “prepare themselves for the final annexation of the earth by God’s heavenly kingdom” (p.42).

What made spirituality particularly appealing to Americans at the time was the rise of industrialization and the changing economy. Wayland-Smith writes that “rural New England during the colonial period and early Republic had been a relatively classless society” and “nineteenth-century Americans were initially horrified by the specter of individual self-seeking and competition run amok that they glimpsed in the new economic system” (p.42-43).

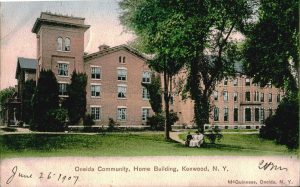

To Noyes’ initial converts, the Oneida Community served as a refuge, an income-sharing alternative to factory labor. Members worked around six hours per day on canning, textile-making, and other tasks, many of which “were performed by ‘bees,’ voluntary gatherings of men, women, and children to share the work and make it pass more pleasantly” (p.86).

As the community grew – with over 200 people living in a single Mansion House – the group relied on a practice called “Mutual Criticism” to address interpersonal issues. A member would be “confronted with an exhaustive list of his faults and failings” as a kind of purification process. “Criticisms were not wholly negative, but judiciously larded with praise, in order to counteract the naturally demoralizing effect of having one’s character flayed before a live audience” (p.107). Sounds a bit like the feedback circles my own community uses!

But things got a bit awkward with the introduction of “complex marriage,” a kind of free love arrangement in which members were forbidden from falling into “sticky love” (that is, monogamous coupling) but instead were expected to share each other as freely as they did their work and incomes.

Although in theory it was the sex-positive lifestyle of its day (members practiced forms of Tantric sex and birth control at a time when discussing birth control was itself illegal), it allowed Noyes to dictate who could and could not reproduce. This culminated in a kind of eugenics program known as “stirpiculture,” in which Community members would selectively breed themselves in an attempt to produce superior offspring.

But the next generation had a very different idea of what the community should look like, and Noyes’ descendants weren’t so keen on Christianity, complex marriage, and income-sharing. The Oneida Community, Limited went into business as a joint-stock company, and for the next century produced some of America’s most popular silverware. There’s a good chance the forks and knives you grew up eating with were produced by the descendants of John Humphrey Noyes!

You’ll have to read the book to find out what happened next. Pick it up from your local bookstore or library to read the whole story!