Student researcher from the University of Amsterdam, Yannick Kiesel, shares the core findings of his Masters Thesis on life in a cohousing community. The research illustrates a new holistic view on cohousing and its complexities. Thanks for sharing Yannick!

My research focused on the sustainable and pro-social communities that tackle the adverse effects of growing urban areas, such as sense of anonymity, lack of adequate and affordable housing, as well as pollution, for which there is a growing need for energy efficiency and green solutions in light of climate change. The Netherlands is home to multiple intentional communities that fall within this category; a phenomenon that began way back in the 1960s. They vary in type, size and age and thus offer a plethora of opportunities for intentional community studies.

For my case study, I chose a comparatively large cohousing community called “De Kersentuin” (eng.: The Cherry Garden; figure 1) which is located south of Amsterdam in the urban area of Utrecht. This cohousing community is considered relatively old, and celebrated its 15th anniversary in 2018. “De Kersentuin” consists of approximately 100 households; two thirds of these are privately owned and the remaining units are rented out. Altogether, this cohousing project is home to approximately 200 residents.

The concept of cohousing is largely based on building a sense of community. Things like small hierarchies in the organization and increased self-reliability in the participation of custom-made solutions are key factors in fostering a sense of community among residents, and thus vital in successful cohousing projects. Additional characteristics like participatory processes in decision- making, extensive common facilities, exclusive resident management, and intentional physical design with private and collective ownership are other elements that make cohousing projects a unique form of an urban living environment. All of these elements are designed and brought to life through the ideas of soon-to-be residents, and therefore create an inimitable project tailored to the needs of its residents. The goal of my research was to investigate this living space using ethnographic methods to gain better understanding of what community characteristics create a successful sustainable urban living project.

During the course of my research, I spent three months conducting daily visits to the project, getting to know the community members, and achieving a primary level of integration. I participated in all kinds of activities offered by the project like regular communal gardening, coffee mornings, evening events and spontaneous encounters. During this time, I had interviews and informal talks with the residents about their community, and carried out a physical analysis of the infrastructure. In addition to objective observation, my research included description of my own experiences and impressions during my time in the cohousing project.

From the beginning, I was warmly welcomed into the community and it was very easy to get in contact with most of the residents. A sense of initiative and a helping hand are always needed, as I was told, so the residents were happy to have some support in their daily work. With time, I came to know most of the active residents by name and could easily spark conversations and interviews about their project. However, as “De Kersentuin” is a relatively big project, it was unfortunately not possible to meet every resident.

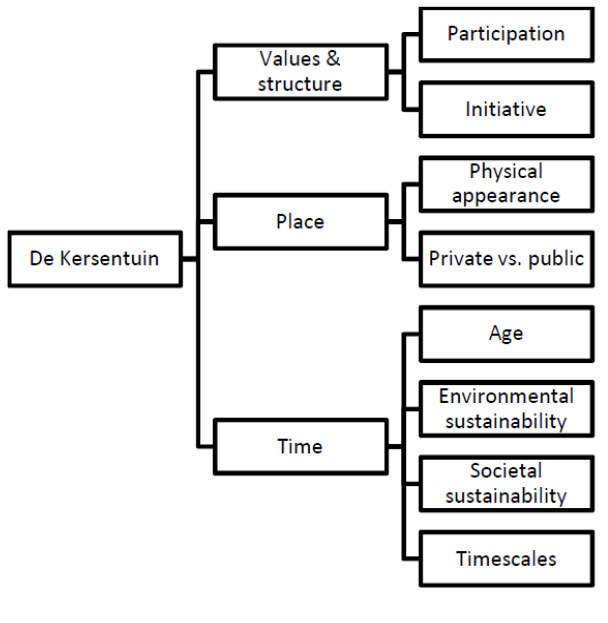

Based on my findings, I chose to organize the data collected into three district categories: values and inner structure, physical appearance, and time.

In terms of values and inner structure, residents value the organizational aspects of the community structure and acknowledge that rules are essential for the survival of the community. In this community, there is absence of hierarchy, meaning that resident decision making is consensus based. Due to the project’s size and total residents, this often leads to prolonged community meetings until an overall agreement is met. Although decisions often do not please everyone, residents realize that compromises must be made in order to maintain a positive development of the community. This organizational structure also gives residents the chance to organize events or workshops independently and thus share common values and interact on a basis of shared interests. Together with a strong sense of commitment, a do-it-yourself mentality, and willingness of the members to invest time, effort, and their own values and intentions, the community is successfully managed on a bases of equality and self- reliance, that allow both individualization and community-building at the same time. Additionally, environmentally friendly behavior defines a key value of the community members in order to create a sense of community. The connection to nature (e.g. through garden activities) and unified climate action (e.g. energy efficiency) are important elements in this cohousing project and many members can identify with it. The residents often insist on separating a sustainable community into two dimensions: the societal sustainability (age-development, interdependence) and the environmental sustainability (green behavior, climate action).

In terms of physical appearance, I found that the satisfaction with the physical appearance of the project contributes to increased social well-being, and possibly a higher degree of participation. The interaction spaces like the gardens and the common areas as well as the creation of symbolic space (giving the space a meaning by practicing a specific event, e.g. singing, playing cards etc.) give residents the chance to use these spaces in specific ways so that they are able to share their interests with other neighbors and outsiders. In this way, the space of De Kersentuin incorporates the common values and practices of the community. Additionally, “encroachment zones” (zones that are not clearly detectable as private or public space, e.g. benches in front of the house, open front gardens) inside the project blur the lines between public and private space, in which residents can decide to share their space with others or maintain their own privacy.

Time and different temporal dimensions are an especially important category, as these were found to define the boundaries of practices, activities and social interactions. To illustrate, consider time as a factor of organization. The residents created different timescales through their organizational structure. These timescales are regularity (e.g. regular events like the weekly gardening activity), daily interactions (e.g. spontaneous meetings and conversations), individual time scopes (e.g. time a new resident needs to integrate into the community), and seasons (e.g. yearly seasons, but also self- created seasons like the gardening season). Residents realize that time and regularity is key to the project’s organization and maintaining a shared schedule and social cohesion. Time can also be considered a measure of the project’s longevity as both the housing project itself and its residents age with time. This presents a certain degree of uncertainty and risk, wherein aging residents can demonstrate a decline in participation. A resident specifically stated that the “aging factor” is considered a serious issue, and even though residents are often joking about growing old together, they still don’t know how it will turn out or what problems could arise.

Together, the findings discussed here illustrate the complexity of cohousing projects and provide opportunity for a holistic view of factors that play into a successful development process (see figure 2). Every cohousing project is unique, however, defining characteristics seem to include the people that are living in said projects and their journey in creating this unique community that is able to

tackle the symptoms of anonymity and indifference in growing urban areas. Cohousing presents an interesting opportunity to combine city living with the sense of community often characteristic of smaller, rural areas. More importantly, cohousing has the potential to shift today’s city housing towards a more pro-social, environmentally friendly urban living. Cohousing projects such as the one described here demonstrate a successful and sustainable living alternative. It is my hope that shedding light on such successful projects will not only emphasize the importance of such solutions, but eventually influence the way we live and interact with one another, and eventually, gain the ability to influence urban policy structures and challenge the current urban living status-quo.

Following are several statements of interest from De Kersentuin residents:

“The thing that you know your neighbors, that you have shared interests, shared activities and most people have the same idea of how they want to live, respect for the environment, respect for social cohesion and what I like very much is that you have your own house and still you live together with other people so you have your freedom but you’re not alone.”

“I think that really keeps the community together and the fact that there are different kinds of activities also show, also gives an opportunity for people with different interests. Because not everybody is interested in gardening or not everybody is interested in music, sometimes they have something with books or something like that, so the variety makes that people can participate in the things they like, they can choose.”

“[…] It feels safe and it feels like a family I think, […] you have so many social contacts here, […] you can find everything here in our two streets and for me that’s great, because it’s difficult when you don’t have a car, it’s difficult to drive to friends […]. So my family, I don’t see so many times because they live too far away, but it’s okay because I have my second family right here.”

“Well, the fact that the inhabitants built it together, that this is really our, this is our neighborhood, our little village within the city, and because this whole process of planning and what will we do and what can we do and all kinds of groups have been looking at the technical side of things but also the social side of things and how we could communicate together and what will be the rules of De Kersentuin this has created this tightly knit group. […] They thought about everything.”

“[…] If I had to be friends with 200 people or a hundred people I would have become mad. For me, that wouldn’t work, […] that’s impossible. What I like here is that you that you have the opportunity to have connections on different levels. So some people […] have become like friends, others occasionally, you have something together, a feeling of connectedness, others you almost never see or you’re not really interested in , […] it’s those different levels. There is not an obl igation to be friends with everybody.”

“[…] we put it on our website, we said “it shows that you can leave a lot more to citizens than many municipalities think you can leave to them”. And we’ve done it, we’ve built a neighborhood and we’re maintaining it, and we’re already doing that for 15 years. So the power of the citizens is much larger than many municipalities dare to believe […] or don’t want to believe.”

“[…] one of the things we […] proof is how much you can do in a very small area, because we have playgrounds, we have meeting places, we have places to relax, we have places which are really maintained with meadows and with mowing every week but we have also a kind of wild nature where the nature goes its way and the only intervention is only limited. We have […] theatre, we have even a small forest, we have a lot of small and bigger fruits, so that there is so much variety, multifunctionality possible in a very small area which I think is proven very well here. “

“While my talk with a resident, we are sitting on a self-built bench, in the sunshine, looking at the garden we were working on the last hours and what we have created. We are watching the remaining neighbors engaging in the garden, interacting, laughing and having fun. A slight feeling of satisfaction spreads out through my body. Is this the ideal situation residents are aiming for in this community?” (own field notes)

Certainly not all results of this research could be fit in this article. For more information, please find the whole master thesis at: https://cohousing.org.uk/information/research/

Figure 1.: Bird eye view over De Kersentuin

Figure 2.: De Kersentuin’s characteristics for a sustainable community