Laird Schaub served as the Executive Director of the FIC from when there was such a position till 2016. Full bio below.

For other 30th blog posts click here.

When a collection of die-hard community veterans gathered at Stelle, IL to coalesce into the Foundation for Intentional Community in May, 1987, we were breaking new ground. To our knowledge, no one had previously tried to form a continental community network before and we were pretty excited to see what we could do. A year later, at our third Board meeting (at Green Pastures, an Emissary of Divine Light community in Epping NH that no longer exists), we’d moved beyond the question of who we were, to focus on what we would do.

When a collection of die-hard community veterans gathered at Stelle, IL to coalesce into the Foundation for Intentional Community in May, 1987, we were breaking new ground. To our knowledge, no one had previously tried to form a continental community network before and we were pretty excited to see what we could do. A year later, at our third Board meeting (at Green Pastures, an Emissary of Divine Light community in Epping NH that no longer exists), we’d moved beyond the question of who we were, to focus on what we would do.

In addition to opening dialog among communities of different stripes (many of whom were not used to talking with one another), we enthusiastically settled on the idea of taking advantage of our breadth—among us, we had contacts all over the continent—to produce a new, improved directory of intentional communities. While Communities magazine had been periodically producing directories since it started publishing in 1972, the latest effort to cover this dynamic field of information was Bobbi Corcoran’s New Age Community Guidebook, released in 1985, and we figured we could produce something much more comprehensive and up-to-date.

The first thing we did was assemble a competent and dedicated crew. Geoph Kozeny, the peripatetic communitarian, temporarily settled at Sandhill Farm (my home community) where we put together the core of our production team. Along with Geoph and me, we got yeoman service from Becca Krantz, Chris Roth (now the Editor of Communities magazine) Anne Beck, and Elke Lerman. Off site we had substantial help from Dan Questenberry, Jenny Upton, and Julie Mazo (all from Shannon Farm in Acton VA), Chris Collins (New Haven CT), and Jim Estes (Alpha Farm in Deadwood OR).

While we naively thought we could complete work in six months, it took 18. As this was the FIC’s first project, we got a crash course in producing work on deadlines with an all-volunteer staff, relying on authors whose only compensation was notoriety and a complimentary copy of the book. It was hard to keep everything on schedule, and we constantly sacrificed timeliness for quality. In addition, it turned out to be like pulling teeth getting communities to send us information about themselves. Every time we asked groups to send us entries we got a 20% response rate, so it took several rounds before we decided we had enough to go to print.

Finally, you have to understand the context. All of this work was accomplished in 1989-90, while the Internet was still basically a novelty. (Email transmissions would come in so slowly back then that you could read them as they were being downloaded. Albert Bates at The Farm experimented with sending us a picture—it took six hours to download and cost $100. Those were the days.)

• The first Directory counted as double issue of Communities magazine (issues #77-78), as we tried to breathe life into the Community Movement’s flagship periodical, which was not coming out regularly those days. While we eventually negotiated with Charles Betterton to become the publisher in 1992, and spun the Directory off as a separate publication, our initial effort helped fulfill overdue obligations to subscribers.

• This edition contained two special features that were not repeated after the second edition (because they took too much work):

—An extensive Resource section for people wanting access to information about cooperative culture that went beyond which intentional communities were where and what were they doing. This included a cornucopia of data about natural building techniques, food preservation, alternative energy, right livelihood, and references to sister networks.

—The infamous RRDDLNoR section (Regrouped, Renamed, Dead, Disbanded, Lost, and No Response). We figured that a lot of seekers would search for a group by name, and it might be precious to learn what had become of a community that was not listed. It was kind of like the deal letter file at the Post Office. We printed several pages of one-line information about groups that didn’t list in the book. (This actually tuned out to be trickier than you might think: sometimes two different people, both purporting to be community representatives, would give us conflicting stories about the group’s status; sometimes we’d learn that a group was defunct, only to get a note six months later that they’d come back to life. You had to keep a close eye on those corpses.)

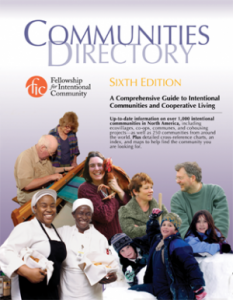

• In those early days FIC had a lot of ideas but no money. To raise funds for production we pre-sold copies for the magnificent sum of $6. When it came out the Directory sold for $12, plus $1.50 s&h. Talk about a deal! The book listed 325 communities in the US, and we sold out three printings—18,000 copies over five years. By way of reference, our online Directory today lists 1086 US groups. The movement has grown and so have we.

• One night Geoph & Dan stayed up late and cooked up the harebrained idea of listing communities alphabetically backwards—from Z to A. I laughed, but used my prerogative as project manager to nix that goofball suggestion (we were trying to be user friendly, right?).

• We had trouble with the first printing because it was perfect bound (meaning the pages were glued to the spine). In a book that’s opened and closed as often as the Directory, it wasn’t long before pages started falling out. Oops! In future editions we corrected that by having the signatures stitched (which is styled “smyth sewn” in the binding business). It cost more but the pages stayed put.

• Geoph first saw a copy of the published book when he accidentally bumped into Don Pitzer (the head of the National Historic Communal Studies Association at the time) in the men’s room of an interstate rest area. How’s that for a serendipitous pee? As Don was wont to say, “It was an historic moment.”

—

Laird lived for nearly four decades (1974-2013) at Sandhill Farm, an income-sharing rural community in Missouri that he helped found. After that he lived for two years at Dancing Rabbit, a Missouri ecovillage trying to model high-quality living using only 10% of the resources of the average American. He’s worked with more than 100 intentional communities, both as a trainer and as an outside facilitator to help groups navigate anaerobic dynamics and organizational snarls. His specialty is up-tempo meetings that engage the full range of human input, teaching groups to work constructively with conflict, and at the same time being ruthless about about capturing as much product as possible.

Laird lived for nearly four decades (1974-2013) at Sandhill Farm, an income-sharing rural community in Missouri that he helped found. After that he lived for two years at Dancing Rabbit, a Missouri ecovillage trying to model high-quality living using only 10% of the resources of the average American. He’s worked with more than 100 intentional communities, both as a trainer and as an outside facilitator to help groups navigate anaerobic dynamics and organizational snarls. His specialty is up-tempo meetings that engage the full range of human input, teaching groups to work constructively with conflict, and at the same time being ruthless about about capturing as much product as possible.